Hello! In today's lesson, we'll talk about Java Exceptions. Everyday life is full of situations that we don't anticipate. For example, you get up for work in the morning and look for your phone charger, but you can't find it anywhere. You go to the bathroom to shower only to discover that the pipes are frozen. You get in your car, but it won't start. A human is able to cope with such unforeseen circumstances quite easily. In this article, we'll try to figure out how Java programs deal with them. ![Exceptions in Java - 2]() The ability to prevent and resolve exceptional situations in a program, allowing it to continue running, is one reason for using exceptions in Java. The exception mechanism also lets you protect your code (API) from improper use by validating (checking) any inputs.

Now imagine that you're the transportation department for a second. First, you need to know the places where motorists can expect trouble. Second, you need to create and install warning signs. And finally, you need to provide detours if problems arise on the main route.

In Java, the exception mechanism works in a similar way. During development, we use a try block to build an "exception barriers" around dangerous sections of code, we provide "backup routes" using a catch {} block, and we write code that should run no matter what in a finally{} block.

If we can't provide a "backup route" or we want to give the user the right to choose, we must at least warn him or her of the danger. Why? Just imagine the indignation of a driver who, without seeing a single warning sign, reaches a small bridge that he cannot cross!

In programming, when writing our classes and methods, we can't always foresee how they might be used by other developers. As a result, we can't foresee the 100% correct way to resolve an exceptional situation. That said, it's good form to warn others about the possibility of exceptional situations.

Java's exception mechanism lets us do this with the throws keyword — essentially a declaration that our method's general behavior includes throwing an exception. Thus, anyone using the method knows he or she should write code to handle exceptions.

The ability to prevent and resolve exceptional situations in a program, allowing it to continue running, is one reason for using exceptions in Java. The exception mechanism also lets you protect your code (API) from improper use by validating (checking) any inputs.

Now imagine that you're the transportation department for a second. First, you need to know the places where motorists can expect trouble. Second, you need to create and install warning signs. And finally, you need to provide detours if problems arise on the main route.

In Java, the exception mechanism works in a similar way. During development, we use a try block to build an "exception barriers" around dangerous sections of code, we provide "backup routes" using a catch {} block, and we write code that should run no matter what in a finally{} block.

If we can't provide a "backup route" or we want to give the user the right to choose, we must at least warn him or her of the danger. Why? Just imagine the indignation of a driver who, without seeing a single warning sign, reaches a small bridge that he cannot cross!

In programming, when writing our classes and methods, we can't always foresee how they might be used by other developers. As a result, we can't foresee the 100% correct way to resolve an exceptional situation. That said, it's good form to warn others about the possibility of exceptional situations.

Java's exception mechanism lets us do this with the throws keyword — essentially a declaration that our method's general behavior includes throwing an exception. Thus, anyone using the method knows he or she should write code to handle exceptions.

![Exceptions in Java - 3]()

![Exceptions in Java - 4]() When an exception is thrown in a try block, the JVM looks for an appropriate exception handler in the next catch block. If a catch block has the required exception handler, control passes to it. If not, then the JVM looks further down the chain of catch blocks until the appropriate handler is found.

After executing a catch block, control is transferred to the optional finally block.

If a suitable catch block is not found, then JVM stops the program and displays the stack trace (the current stack of method calls), after first performing the finally block if it exists.

Example of exception handling:

When an exception is thrown in a try block, the JVM looks for an appropriate exception handler in the next catch block. If a catch block has the required exception handler, control passes to it. If not, then the JVM looks further down the chain of catch blocks until the appropriate handler is found.

After executing a catch block, control is transferred to the optional finally block.

If a suitable catch block is not found, then JVM stops the program and displays the stack trace (the current stack of method calls), after first performing the finally block if it exists.

Example of exception handling:

What's an Java exception?

In the programming world, errors and unforeseen situations in the execution of a program are called exceptions. In a program, exceptions can occur due to invalid user actions, insufficient disk space, or loss of the network connection with the server. Exceptions can also result from programming errors or incorrect use of an API. Unlike humans in the real world, a program must know exactly how to handle these situations. For this, Java has a mechanism known as exception handling.A few words about keywords

Exception handling in Java is based on the use of the following keywords in the program:- try - defines a block of code where an exception can occur;

- catch - defines a block of code where exceptions are handled;

- finally - defines an optional block of code that, if present, is executed regardless of the results of the try block.

- throw - used to raise an exception;

- throws - used in the method signature to warn that the method may throw an exception.

// This method reads a string from the keyboard

public String input() throws MyException { // Use throws to warn

// that the method may throw a MyException

BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in));

String s = null;

// We use a try block to wrap code that might create an exception. In this case,

// the compiler tells us that the readLine() method in the

// BufferedReader class might throw an I/O exception

try {

s = reader.readLine();

// We use a catch block to wrap the code that handles an IOException

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

// We close the read stream in the finally block

} finally {

// An exception might occur when we close the stream if, for example, the stream was not open, so we wrap the code in a try block

try {

reader.close();

// Handle exceptions when closing the read stream

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

}

}

if (s.equals("")) {

// We've decided that an empty string will prevent our program from working properly. For example, we use the result of this method to call the substring(1, 2) method. Accordingly, we have to interrupt the program by using throw to generate our own MyException exception type.

throw new MyException("The string cannot be empty!");

}

return s;

}

Why do we need exceptions?

Let's look at an example from the real world. Imagine that a section of a highway has a small bridge with limited weight capacity. If a car heavier than the bridge's limit drives over it, it could collapse. The situation for the driver would become, to put it mildly, exceptional. To avoid this, the transportation department installs warning signs on the road before anything goes wrong. Seeing the warning sign, a driver compares his or her vehicle's weight with the maximum weight for the bridge. If the vehicle is too heavy, the driver takes a bypass route. The transportation department, first, made it possible for truck drivers to change their route if necessary, second, warned drivers about the dangers on the main road, and third, warned drivers that the bridge must not be used under certain conditions. The ability to prevent and resolve exceptional situations in a program, allowing it to continue running, is one reason for using exceptions in Java. The exception mechanism also lets you protect your code (API) from improper use by validating (checking) any inputs.

Now imagine that you're the transportation department for a second. First, you need to know the places where motorists can expect trouble. Second, you need to create and install warning signs. And finally, you need to provide detours if problems arise on the main route.

In Java, the exception mechanism works in a similar way. During development, we use a try block to build an "exception barriers" around dangerous sections of code, we provide "backup routes" using a catch {} block, and we write code that should run no matter what in a finally{} block.

If we can't provide a "backup route" or we want to give the user the right to choose, we must at least warn him or her of the danger. Why? Just imagine the indignation of a driver who, without seeing a single warning sign, reaches a small bridge that he cannot cross!

In programming, when writing our classes and methods, we can't always foresee how they might be used by other developers. As a result, we can't foresee the 100% correct way to resolve an exceptional situation. That said, it's good form to warn others about the possibility of exceptional situations.

Java's exception mechanism lets us do this with the throws keyword — essentially a declaration that our method's general behavior includes throwing an exception. Thus, anyone using the method knows he or she should write code to handle exceptions.

The ability to prevent and resolve exceptional situations in a program, allowing it to continue running, is one reason for using exceptions in Java. The exception mechanism also lets you protect your code (API) from improper use by validating (checking) any inputs.

Now imagine that you're the transportation department for a second. First, you need to know the places where motorists can expect trouble. Second, you need to create and install warning signs. And finally, you need to provide detours if problems arise on the main route.

In Java, the exception mechanism works in a similar way. During development, we use a try block to build an "exception barriers" around dangerous sections of code, we provide "backup routes" using a catch {} block, and we write code that should run no matter what in a finally{} block.

If we can't provide a "backup route" or we want to give the user the right to choose, we must at least warn him or her of the danger. Why? Just imagine the indignation of a driver who, without seeing a single warning sign, reaches a small bridge that he cannot cross!

In programming, when writing our classes and methods, we can't always foresee how they might be used by other developers. As a result, we can't foresee the 100% correct way to resolve an exceptional situation. That said, it's good form to warn others about the possibility of exceptional situations.

Java's exception mechanism lets us do this with the throws keyword — essentially a declaration that our method's general behavior includes throwing an exception. Thus, anyone using the method knows he or she should write code to handle exceptions.

Warning others about "trouble"

If you don't plan on handling exceptions in your method, but want to warn others that exceptions may occur, use the throws keyword. This keyword in the method signature means that, under certain conditions, the method may throw an exception. This warning is part of the method interface and lets its users implement their own exception handling logic. After throws, we specify the types of exceptions thrown. These usually descend from Java's Exception class. Since Java is an object-oriented language, all exceptions are objects in Java.

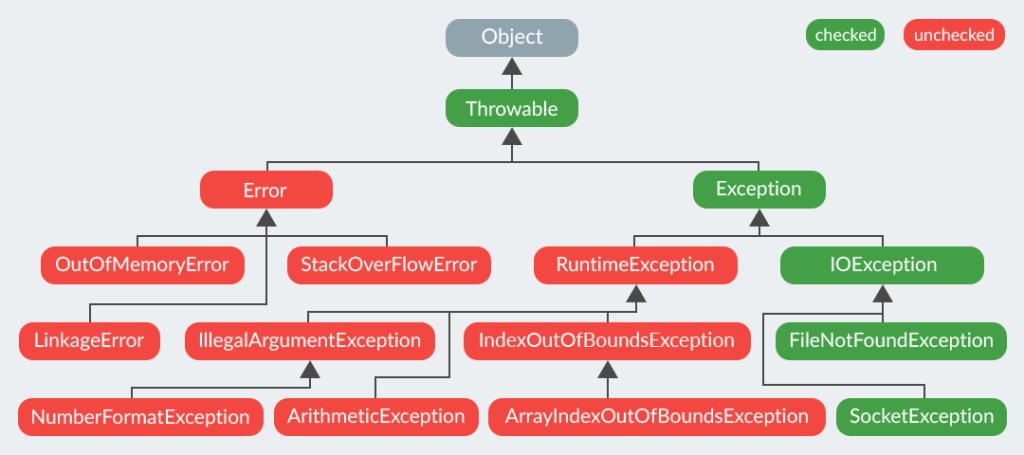

Exception hierarchy

When an error occurs while a program is running, the JVM creates an object of the appropriate type from the Java exception hierarchy — a set of possible exceptions that descend from a common ancestor — the Throwable class. We can divide exceptional runtime situations into two groups:- Situations from which the program cannot recover and continue normal operation.

- Situations where recovery is possible.

Creating an exception

When a program runs, exceptions are generated either by the JVM or manually using a throw statement. When this happens, an exception object is created in memory, the program's main flow is interrupted, and the JVM's exception handler tries to handle the exception.Exception handling

In Java, we create code blocks where we anticipate the need for exception handling using the try{}catch, try{}catch{}finally, and try{}finally{} constructs. When an exception is thrown in a try block, the JVM looks for an appropriate exception handler in the next catch block. If a catch block has the required exception handler, control passes to it. If not, then the JVM looks further down the chain of catch blocks until the appropriate handler is found.

After executing a catch block, control is transferred to the optional finally block.

If a suitable catch block is not found, then JVM stops the program and displays the stack trace (the current stack of method calls), after first performing the finally block if it exists.

Example of exception handling:

When an exception is thrown in a try block, the JVM looks for an appropriate exception handler in the next catch block. If a catch block has the required exception handler, control passes to it. If not, then the JVM looks further down the chain of catch blocks until the appropriate handler is found.

After executing a catch block, control is transferred to the optional finally block.

If a suitable catch block is not found, then JVM stops the program and displays the stack trace (the current stack of method calls), after first performing the finally block if it exists.

Example of exception handling:

public class Print {

void print(String s) {

if (s == null) {

throw new NullPointerException("Exception: s is null!");

}

System.out.println("Inside print method: " + s);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Print print = new Print();

List list= Arrays.asList("first step", null, "second step");

for (String s : list) {

try {

print.print(s);

}

catch (NullPointerException e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

System.out.println("Exception handled. The program will continue");

}

finally {

System.out.println("Inside finally block");

}

System.out.println("The program is running...");

System.out.println("-----------------");

}

}

}

Inside print method: first step

Inside finally block

The program is running...

-----------------

Exception: s is null!

Exception handled. The program will continue

Inside finally block

The program is running...

-----------------

Inside print method: second step

Inside finally block

The program is running...

-----------------

public String input() throws MyException {

String s = null;

try (BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in))){

s = reader.readLine();

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

}

if (s.equals("")) {

throw new MyException ("The string cannot be empty!");

}

return s;

}

public String input() {

String s = null;

try (BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in))) {

s = reader.readLine();

if (s.equals("")) {

throw new MyException("The string cannot be empty!");

}

} catch (IOException | MyException e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

}

return s;

}

GO TO FULL VERSION